14. How Can You Be Fully Conscious Without Most of Your Brain?

Extraordinary cases of people living full lives with minimal brain tissue may point to a new way of understanding consciousness

It sounds impossible, but it’s real.

In France, a civil servant lived a normal family life and held a steady job despite having a brain so compressed and reduced that scans showed barely 10% of typical mass. In another case, a student completed a degree while carrying inside his skull what neurologists described as “paper-thin” cortical tissue.

Stories like these throw a monkey wrench into everything we think we know about consciousness. The standard model says the brain produces the mind, and the more brain you lose, the more you lose yourself. Yet here are people whose “hardware” is almost entirely gone, still thinking, feeling, and engaging with the world.

If the factory that supposedly makes the product is mostly missing, how can the product still exist? The answer may be that the brain isn’t a factory at all, it’s a receiver. And as long as the right components of that receiver remain, the signal of consciousness can still come through.

Case Studies That Break the Rules

If you’ve ever doubted how little brain matter a person can live with, consider these examples. These examples upend long-held assumptions about how much brain matter is needed for consciousness.

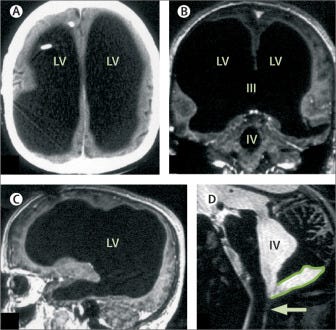

1. The Civil Servant with Hydrocephalus

In 2007, French doctors ran brain scans on a 44-year-old man after he came in complaining of mild weakness in one leg. What they saw was astonishing: almost his entire cranial cavity was filled with cerebrospinal fluid, leaving only a thin rind of brain tissue pressed against the inside of his skull. Yet nothing in his life suggested anything was wrong. He worked steadily as a civil servant, was married with two children, and handled everyday life without difficulty. His IQ tested at 75, low-average but far from debilitating. The case raised a stark question: how could someone function so well with a brain that, by volume, was mostly missing1?

Feuillet et al/The Lancet

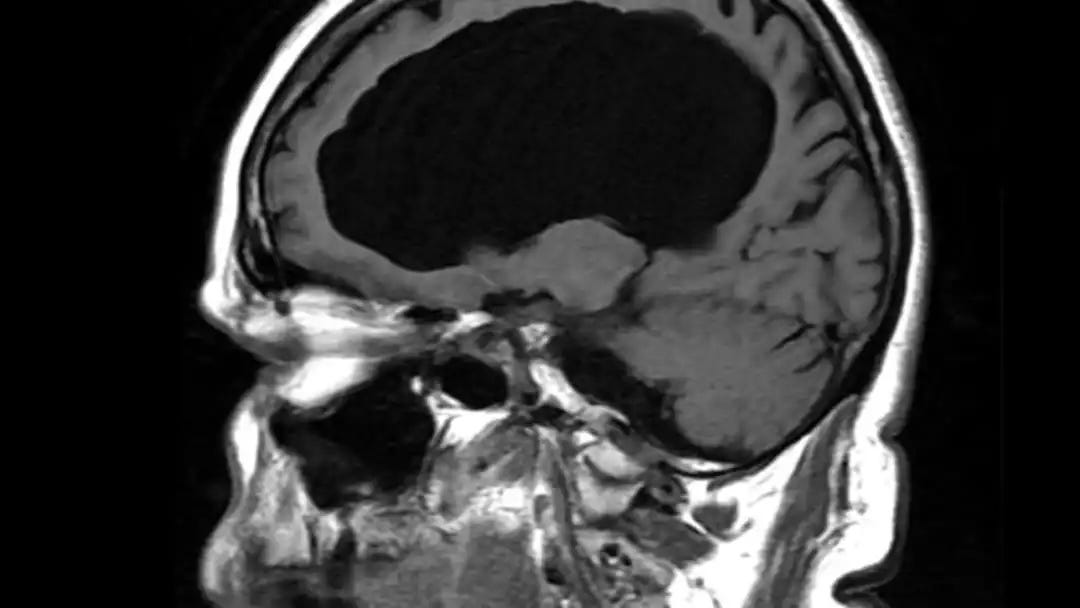

2. The Math Student with Virtually No Cortex

Neurologist John Lorber became known for investigating unusual hydrocephalus cases. One of the most famous involved a mathematics student at Sheffield University whose brain scans showed only a thin layer of cortex, with the rest of the skull filled by fluid. On paper, this should have been devastating. Instead, the student earned a first-class degree and had an IQ of 126, well above average. Lorber cataloged hundreds of patients with similarly extreme cortical reduction who still lived independent, cognitively normal lives. The pattern was impossible to ignore: losing the majority of your brain’s mass didn’t necessarily erase the mind2.

Radiopaedia | Radiopaedia

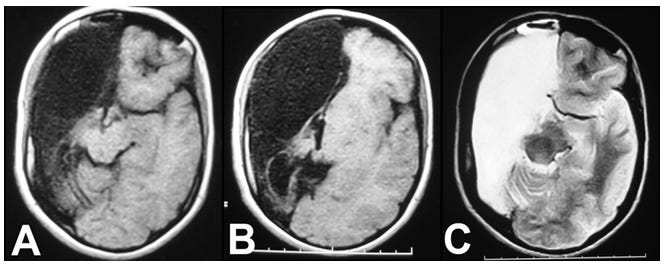

3. The Boy Born with Half a Brain

In one rare case, a boy diagnosed with hemihydranencephaly, the complete absence of one cerebral hemisphere, grew up with surprisingly normal cognitive and language abilities. Scans revealed that the missing hemisphere had been replaced entirely by fluid, yet the remaining half of his brain, along with brainstem and peripheral systems, compensated enough for him to attend school, communicate effectively, and engage socially. He showed mild weakness on one side of his body but lived an otherwise ordinary life, defying expectations for such a profound structural absence3.

Tehran University of Medical Sciences

These cases stand as living counterarguments to the belief that consciousness scales neatly with brain mass. If sheer volume were everything, these individuals should have been profoundly impaired or entirely unconscious. Instead, they suggest that consciousness depends less on the total quantity of brain tissue and more on whether the critical reception-and-processing components remain intact. What we’ll call the Minimum Viable Receiver.

The Limits of the Brain-as-Factory Model

Modern neuroscience often treats the brain as a factory. Raw sensory inputs go in, mental experience comes out. The assumption is straightforward: more machinery means greater capacity, and losing significant portions of it should cripple or erase consciousness. Under this view, there’s a direct relationship between the quantity of functioning brain tissue and the quality or presence of awareness.

The cases we’ve just examined make that logic difficult to sustain. If consciousness truly scaled with brain mass, the French civil servant with a thin rind of cortex should not have been able to work, raise a family, or manage daily life. The mathematics student with a paper-thin cortex should not have earned a first-class degree. The boy with only one hemisphere should not have developed normal language and social abilities. Yet each did.

This pattern forces a reconsideration of the brain’s role. Perhaps the most surprising part is that the evidence is not limited to a few anomalies tucked away in obscure journals. Similar cases, though rare, have been observed repeatedly across decades of neurology. And in each, the deciding factor appears to be which structures remain functional, not how much brain tissue is present overall.

When damage strikes the brainstem or specific integrative hubs, consciousness can vanish in an instant, even if the rest of the brain is intact. But when the damage is spread across less critical regions, awareness can persist despite enormous loss of volume. This discrepancy hints at a threshold model — one where the survival of certain key components is enough to keep the lights on.

From a BioCircuit Consciousness Theory (BCCT) perspective, this points toward an alternate framing: the brain’s role may be less about manufacturing consciousness and more about tuning into and shaping a signal that exists independently of it. A receiver can be stripped of many nonessential parts and still pick up a broadcast, as long as the essential circuits for reception and processing are intact. The “factory” metaphor begins to break down, and a more resilient, networked model of consciousness starts to make sense.

The Receiver Hypothesis in BCCT

If the brain isn’t a factory producing consciousness, what is it doing?

BCCT reframes it as the central tuner and processor for a signal that originates outside the brain itself. In this model, consciousness is more like a broadcast — constant, pervasive, and available to any living system capable of locking onto it.

The brain’s role is to select and shape that broadcast into the personal, moment-by-moment experience we call the self. Its networks act like a tuner, scanning for the signal and translating it into coherent perception, memory, and action. The rest of the body participates as an extended antenna array, feeding the brain’s tuner additional information through sensory nerves, the spinal cord, and secondary neural systems such as the gut-brain and heart-brain connections.

When large portions of brain tissue are lost but the core tuning circuits remain intact, the signal can still come through. That’s why the civil servant, the mathematics student, and the boy with half a brain could still think, feel, and live functional lives. They didn’t need the full array of brain structures, only enough of the right ones to capture and process the signal effectively.

This framing also explains why certain injuries, even if small, can eliminate consciousness entirely. Destroy the brainstem’s relay hubs or sever the pathways that integrate signal input, and the receiver can no longer function. The signal is still there, but the tuning system has gone offline.

From here, the question becomes: what is the minimum viable configuration of brain and body needed to maintain signal lock? That’s where the concept of the Minimum Viable Receiver (MVR) comes into focus.

The Minimum Viable Receiver (MVR)

In BCCT terms, the Minimum Viable Receiver is the smallest configuration of brain and body components capable of maintaining a stable lock on the consciousness signal. It’s the difference between catastrophic brain loss, where awareness disappears, and remarkable survival stories where the mind stays fully online despite massive structural reduction.

The MVR depends on the right components functioning in unison, not on having a full brain. The evidence from case studies suggests that the following elements are essential:

Brainstem and Thalamus: The Signal Gateway

These structures are the primary relay and integration hubs for incoming sensory data and outgoing motor commands. The brainstem regulates core functions like breathing and heartbeat, but it also houses reticular activating systems critical for wakefulness and basic awareness. The thalamus acts as a switchboard, routing incoming information to the right cortical areas. If either is destroyed, consciousness often vanishes instantly.Key Cortical Hubs: The Interpretation Layer

Not all cortical regions are equal when it comes to awareness. Evidence points to areas in the frontal and parietal lobes as central for integrating sensory inputs, directing attention, and maintaining a coherent sense of self. These hubs allow the raw signal to be transformed into structured perception, memory, and planning.Connective Pathways: The Synchronization Lines

White matter tracts like the thalamo-cortical loops and corpus callosum maintain coordination between distant brain regions. Even with major tissue loss, if these pathways remain intact, the remaining brain structures can still communicate effectively enough to sustain conscious experience.Bodywide Input Network: The Auxiliary Antenna Array

The nervous system doesn’t end at the skull. Peripheral nerves, the spinal cord, the enteric nervous system, and the heart’s intrinsic neural network all contribute to sensory processing and feedback loops that enrich the brain’s interpretation of the consciousness signal. This distributed reception may explain why some people with extreme brain reduction still process the world coherently — the “antenna” extends beyond the head.

When these elements survive injury or developmental anomalies, even in reduced or restructured form, the receiver can keep working. The resulting consciousness might not be identical to that of an undamaged brain. Subtle deficits may exist in memory, attention, or processing speed, but the core sense of self and moment-to-moment awareness can remain intact.

The MVR concept reframes extraordinary neurological survival not as a baffling exception, but as evidence of how consciousness operates. It suggests that awareness is resilient, less dependent on total brain mass than on a specific set of interconnected components that work as a unified receiver. And it raises a provocative question for neuroscience: if we can identify and protect the MVR, could we one day restore consciousness in cases where it has been lost?

Implications for Neuroscience and Medicine

Viewing the brain as a receiver for consciousness, and identifying the Minimum Viable Receiver, could shift how medicine understands, diagnoses, and treats severe brain injury.

Redefining Prognosis

Conventional prognosis often ties recovery potential to the amount of remaining brain tissue. The MVR model suggests that which structures remain is more important than how much remains overall. This could lead to more precise predictions about recovery and a greater willingness to attempt rehabilitation in cases that would previously be written off.Rethinking Brain Death Criteria

Brain death is currently defined by the irreversible cessation of all brain activity. Yet if the MVR, including critical brainstem and thalamic functions, is still operational, awareness might persist in forms we do not yet measure effectively. This raises both medical and ethical questions about the accuracy of current diagnostic tools.New Rehabilitation Strategies

If consciousness depends on maintaining signal lock, therapies could focus on stabilizing and enhancing the performance of surviving MVR components. This might include targeted stimulation of thalamo-cortical pathways, neuroplasticity training, or even bioelectronic devices designed to reinforce weak but functional circuits.Integration with Whole-Body Health

Because the body’s distributed antenna network contributes to reception, restoring or optimizing peripheral systems such as gut health, cardiovascular function, and sensory pathways might improve the quality of the consciousness signal even in cases of severe brain injury. Rehabilitation could expand beyond the head and include whole-system tuning.Ethical and Philosophical Impact

If consciousness is a broadcast and the brain is a receiver, then losing part of the hardware doesn’t necessarily mean the “person” is gone. This challenges not only clinical definitions but also how we think about personhood, identity, and the persistence of self after injury.

By shifting the focus from quantity of brain tissue to the functionality of the Minimum Viable Receiver, medicine gains a more nuanced framework for understanding survival, recovery, and the boundaries of conscious life.

What We Still Don’t Know

The cases of extreme brain reduction show us that consciousness can be more resilient than traditional models predict. The MVR concept offers a framework for why awareness sometimes survives catastrophic loss, and the distributed reception model widens the scope of what counts as essential to conscious life.

Yet the central mystery remains unsolved. We can map the structures that seem necessary for the signal, but we still don’t know the nature of the signal itself. Where does it originate? How is it shaped by the living systems that receive it? Could it exist independently of biology, waiting for any suitable receiver?

These questions keep consciousness research in open territory, where neuroscience, philosophy, and physics still overlap. If the broadcast model is right, we are only beginning to understand the scope of what it means to be aware. Each case of survival with minimal brain matter is not just a medical curiosity, but a clue that the signal of consciousness might be far more universal, and far less fragile, than we have assumed.

Feuillet, Luc, et al. “Brain of a White-Collar Worker.” The Lancet, vol. 370, no. 9583, 2007, p. 262. Elsevier

Lorber, John. “Hydrocephalus and Intelligence: Report of a Mathematics Student with Severe Cortical Reduction.” Science, vol. 210, no. 4475, 1980, pp. 431–434. American Association for the Advancement of Science

Pavone, P., et al. “Hemihydranencephaly: Living with Half Brain Dysfunction.” Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 2013